Some poems fight you every step of the way. This one did—from its first draft to its final line. It began with toast Frances couldn’t eat.

Not the sandwich at lunch, not the biscuits with her tea. Coeliac disease had turned her world into a minefield of gluten, and that day in Singapore, everything seemed to contain the very thing that would leave her in pain and in danger of slipping into a coma.

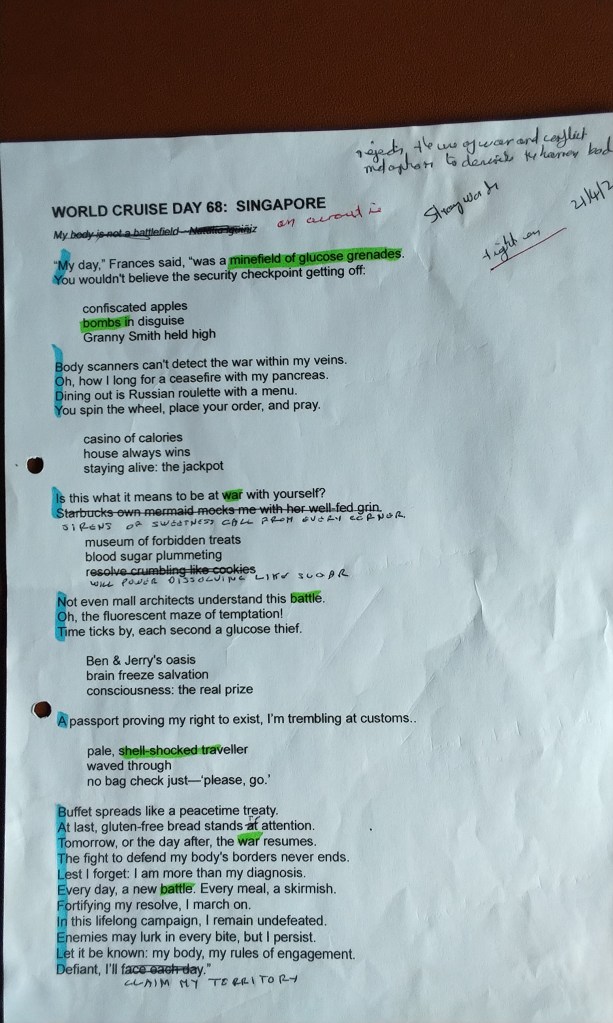

I started with a free verse draft, voice-led, trying to channel Frances’s experience directly. Her words, her frustration, her body’s rebellion against what should have been simple nourishment. It felt right to let the poem breathe in short lines, unforced, raw.

I was pleased enough with it to submit. A few weeks later, it was accepted. Except, no contributor copy, no proof. Just an email telling me to buy the magazine if I wanted to see it in print. I’d found the callout on Facebook and hadn’t checked the fine print. My fault entirely. But it stung. I never bought the magazine, never saw my name on the contents page. Does that count as being published? I’m still not sure.

Still, the poem nagged at me. Frances lives with real discomfort, daily limitations. If I was going to write about her experience, shouldn’t the writing cost me something? Shouldn’t I feel some of the tightrope she walks?

I remembered one of her refrains: “My body is not a battlefield.” She hated the military metaphors people lazily applied to illness. I took those six words and built an acrostic around them, weaving five haikus between each one.

It took weeks. I sweated over every syllable, every line break. The constraint forced me to slow down, to pay attention. I thought I’d finally created something that honoured her pain and the challenge of translating it into language.

I thought it was brilliant. Others agreed with me. Frances didn’t.

“It doesn’t quite work,” she said. And when I looked again, especially alongside other poems in my collection, I had to admit she was right. It felt strained: clever, maybe, but ultimately artificial. Like I was trying too hard to be poetic about someone else’s pain. Writing it was like breaking a leg; you don’t want to do it again.

So I rewrote it. In my own voice, with my own metaphor.

I played school cricket once, when I was fourteen. Scored 48 runs, half our total that day. I walked back proud, expecting a nod from the coach. Instead, he tore into me in front of the team: “Stop slogging the ball!” Despite contributing most of our score, I’d failed, apparently, to play the right way.

That stayed with me. I played safe for a long while after that.

So I wrote into that memory. Into the feeling of doing your best, getting it wrong, being misunderstood. Into the helplessness of watching someone you love suffer and not always knowing how to help. That was my way in. I couldn’t write her pain. But I could write about my place beside it.

The cricket metaphor worked because it was mine. It carried the sting of remembered embarrassment, the complexity of good intentions gone awry. It gave me a way to be honest without overreaching.

Sometimes, the best way to honour someone else’s story is to find the place where it intersects with your own. Even if that place is a cricket pavilion, twenty-five years ago, where a boy learned that effort doesn’t always equal approval.

The poem still isn’t perfect. But it’s true in a way the others weren’t.

DAY 68: TRAVEL IS LIKE CRICKET WITHOUT A BOX (SINGAPORE)

Frances is coeliac and diabetic. Travel, for her,

is like cricket: the rules are incomprehensible,

the danger accumulates slowly, and eventually,

something hits you in the gut.

No food allowed ashore. An apple becomes

a threat to National Security.

We should’ve stopped at M&S, filled a bag with snacks

and called them “religious relics.”

Frances shrugs. “Typical. Obey the rules, go hungry.”

We walk the bay, pass sushi bars, bubble tea kiosks,

Hello Kitty blinking from neon signs.

Frances says, “Beautiful city, but everything wants to kill me.”

At Marina Bay Sands, cinnamon spirals

from a doughnut cart, naan sizzles

behind glass. She sits on a low wall,

hands trembling like leaves.

I pass her a fruit pastille. She chews without speaking,

like someone trying to stay conscious through a sermon.

Frances squeezes my hand, once, hard—

for comfort, and to stay upright.

Starbucks has nothing safe.

Just posters smug with gluten.

She sits beside a polished escalator,

face pale, breath shallow.

I’m rehearsing collapse, seeing her fall before she does,

imagining the sound her skull would make on tile.

We ride the subway to another mall—

air-conditioned, endless, engineered to trap the weak.

At passport control, the guard waves us through

with a look that says just go.

Her look says what I won’t:

this is an emergency.

Back on board, the buffet glows

like salvation. She eats slowly.

Colour returns to her cheeks like dawn.

“I feel human again,” she says.

I say nothing, but I think:

God, I love her. Even if sometimes I feel

I’m facing Fred Trueman and I’m not wearing a box.