The phrase is commonly linked to William Faulkner. Its clearer early form appears in a 1914 lecture by Arthur Quiller-Couch. He advised writers:

“Whenever you feel an impulse to perpetrate a piece of exceptionally fine writing, obey it wholeheartedly and delete it before sending your manuscript to press. Murder your darlings.”

In a poetry collection, the darling may be a strong standalone poem that disrupts tonal coherence, a crowd-pleaser that flattens quieter tensions, an early success that no longer matches your current voice, or a poem that repeats work handled better elsewhere. The issue is not quality in isolation. It is fit.

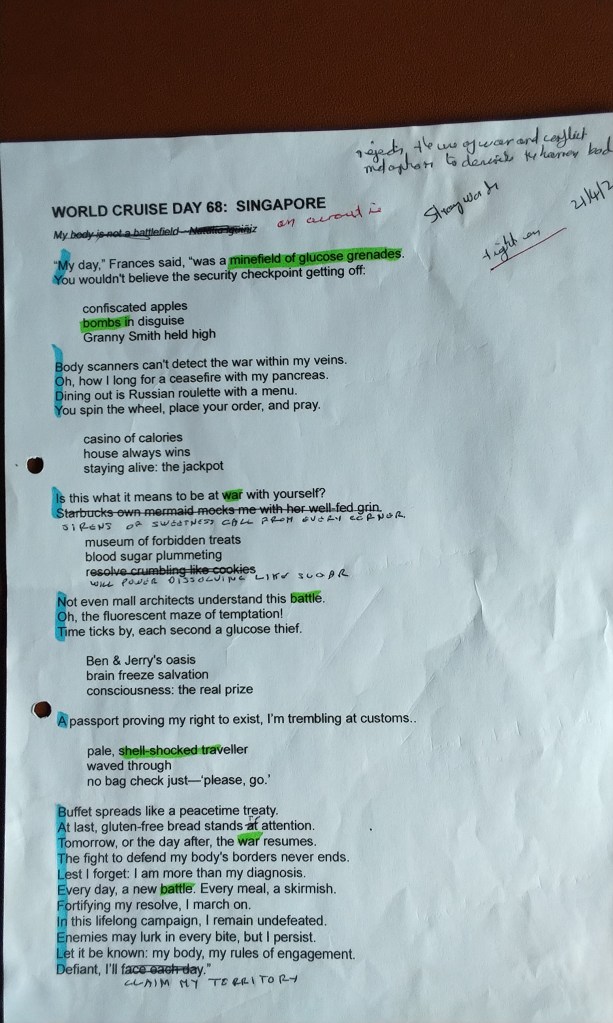

Postcards from the Floating World began with a simple constraint: one poem a day for a 102-day world cruise. The structure felt watertight. Every day accounted for, every port recorded, the calendar as backbone.

A strict calendar can flatten voltage.

When I sent the manuscript to a few friends and then left it alone for two weeks, I came back with different eyes. Not better eyes. Just eyes that had stopped being proud of the project and started reading the poems. I saw a collection that documented the voyage faithfully but in places forgot to be a book.

I hope they agree with me I should cut nine poems. Days 5, 6, 18, 33, 34, 39, 56, 60, and 80.

The reasons vary Some are weak. Some are pleasant but go nowhere. Some cover ground handled better elsewhere. Some could have been written by anyone. Some were too raw, serving me rather than the reader. Some were repetitive.

Removing those days restored pressure to the collection. The gaps do what gaps do. They ask the reader to lean in.

The hardest cut was Day 39. I had called it Exit, a poem about the introvert’s need to slip away from noise and find a quiet corner. I liked it. I revised it carefully. It had a good last line. Read cold, it said exactly what it meant and nothing more. It did not discover anything. It confirmed what the reader already suspected about the speaker and sent them on their way. That may be enough for an essay. It is not enough for a poem.

That is what a darling looks like from the outside. Important to the writer. Explicable. Self-contained. For those reasons, faintly inert on the page.

A collection is an argument in sequence. One poem may be excellent in isolation yet distort pacing, shift register, or introduce a theme the book cannot sustain. Keeping it because it once felt important weakens the whole.

There is a structural economy at stake. Too many high-voltage poems in a row can numb the reader. Too many explanatory poems close down interpretive space. The discipline of cutting is not self-punishment. It is alignment. Asking each poem not just whether it works, but whether it works here, next to these poems, in this order, for a reader who has just come from there and is heading elsewhere.

The 102-day structure was never the point. The voyage was. And the voyage, like all voyages, was not continuous. It had dead days, wasted days, days that led nowhere. Honouring that in the manuscript means keeping some of those days. It also means knowing which serve the book and which serve the calendar.

The calendar, in the end, is not your reader’s problem.

If you are working on a collection and wondering whether a poem belongs, the question is not: is this good? You already know it is good. That is why it is still there.

The question is: does it discover, or does it confirm?

Confirmation is comfortable. Discovery is what the reader came for.

Murder your darlings. They survive the cut. You wrote them. They are already inside everything else.