There’s something almost ceremonial about preparing to write poetry. I sat down with two pristine notebooks, each chosen with careful deliberation. The first would be my workshop – a space for crossings-out, arrows, margin notes, and all the beautiful mess of creation. The second, with its clean pages waiting for careful penmanship, would house the more polished versions, the poems that had emerged from that creative chaos. But as I stared at those blank pages, I realized that good intentions and empty notebooks weren’t enough. I needed more than just space to write – I needed structure, a framework to lean on. Something that would carry me through those grey days when inspiration feels distant, when the words don’t flow easily. Something that would help me know when I’d actually completed a poem, rather than just abandoned it. That’s when I began searching for a form that could serve as both guide and measuring stick.

Diving into Edward Hirsch’s “A Poet’s Glossary,” I searched for forms that could offer both structure and creative freedom. The ten-line decima caught my attention, with its generous allowance of 8-10 syllables per line. But other influences kept tugging at my sleeve: the blues music I’d loved for over five decades, with its raw emotional depth and distinctive rhythm; the elegant pivot of haiku; the passionate yearning in ghazals; the architectural precision of sonnets.

The blues has been my constant companion for over five decades, and its influence runs deeper than just rhythm and rhyme. What draws me to blues music is how it transforms personal pain into shared experience – the way a singer can take a broken heart or an empty pocket and make it resonate with universal truth. Blues lyrics often follow a pattern of statement, development, and resolution, much like the best poems. They build tension through repetition, then release it with a surprising turn. I wanted my poetic form to capture this emotional architecture: the way blues singers can make a simple phrase carry the weight of generations, how they can squeeze hope from despair, or find humour in hardship. It’s not just about sadness – it’s about emotional honesty in all its forms.

My journey to this form wasn’t straightforward. First attempts were too rigid, trying to force every element – blues, ghazal, haiku – into strict coordination. The poems felt mechanical, like they were assembled rather than written. Then I went too far the other way, making the structure so loose it provided no guidance at all. I filled pages with variations, testing different line lengths, playing with where to place the emotional turns. Some versions emphasized the blues elements but lost the lyrical qualities of the ghazal; others maintained formal precision but felt emotionally flat. Each failure taught me something about what I was really seeking: not a cage to contain the poems, but a trellis to help them grow.

The structure I finally developed is meant to be flexible – more like jazz improvisation than classical music. While the basic elements remain constant (ten lines, the emotional arc, the blues influence), poets can adapt them to serve their vision. The syllable count of 8-10 per line is a suggestion rather than a rule – if a seven-syllable line carries the right weight, use it. The couplet structure can be maintained or abandoned as the poem demands. Even the positioning of the various elements can shift: the blues feeling might emerge earlier than lines seven and eight if that’s where the poem wants to go. What matters is maintaining the emotional trajectory: grounding the poem in concrete experience, allowing space for longing and reflection, and finding a way to transform these personal moments into something beautiful, that might appeal to either local or universal audiences.

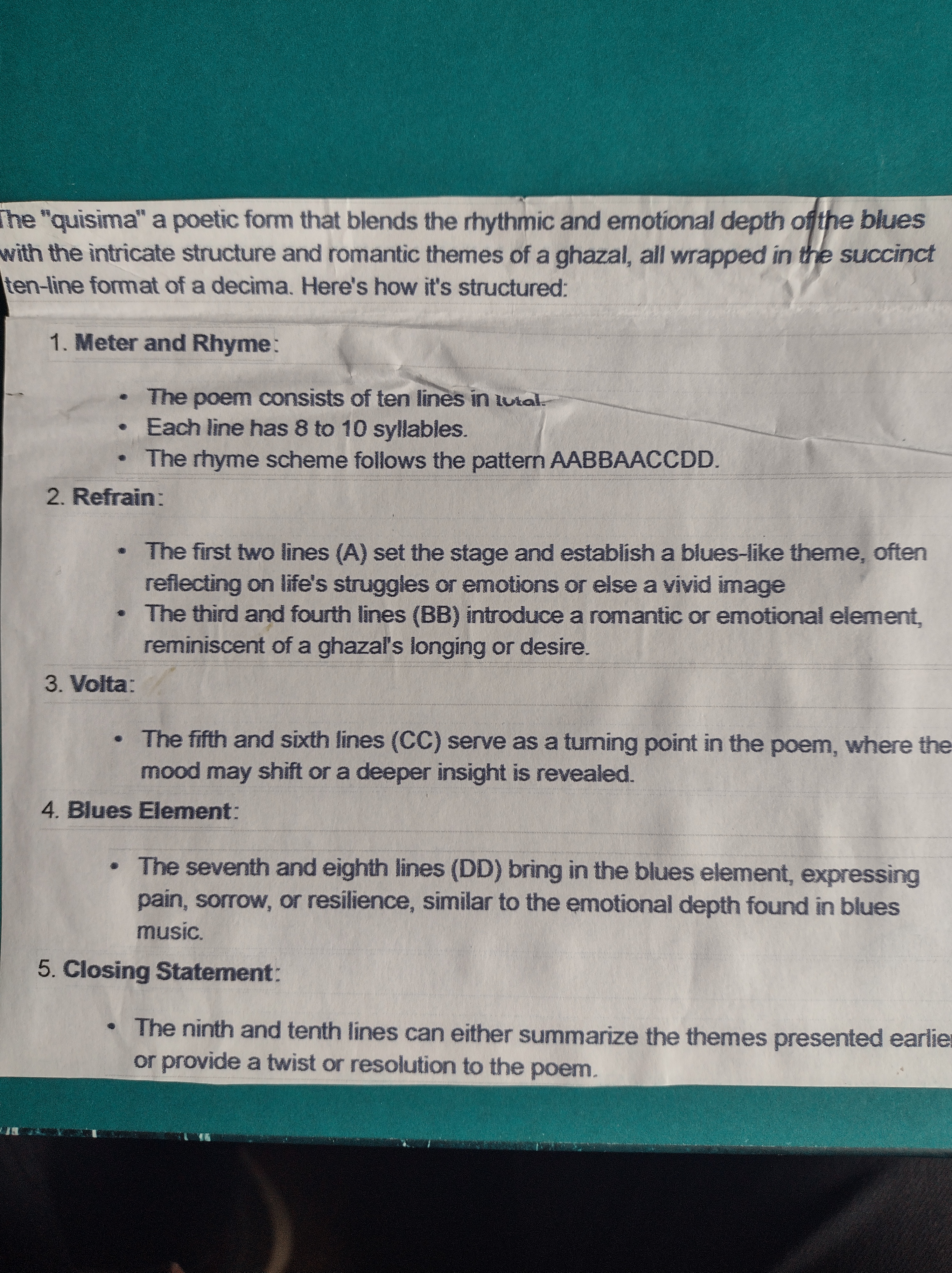

The Structure:

Opening (Lines 1-2):

These lines set the stage, either with a blues-inspired reflection on life’s struggles or a striking image that anchors the poem.

The Heart (Lines 3-4):

Here, I borrow from the ghazal tradition, introducing an element of longing or emotional revelation.

The Turn (Lines 5-6):

This is where the poem pivots, much like a haiku’s cutting word, offering a shift in perspective or a moment of insight.

The Deep Blues (Lines 7-8):

These lines channel the emotional authenticity of blues music, exploring themes of pain, resilience, or raw feeling.

The Resolution (Lines 9-10):

For the closing, I follow Stanley Kunitz’s wisdom: “Always end with an image and don’t explain” (Kunitz & Lentine, 2005, p. 84). These final lines can either gather the threads together or unravel them in an unexpected direction.

Technical Framework:

– Ten lines total

– 8-10 syllables per line

– Couplet structure (though this proved more flexible in practice)

Further Reading:

Ferris, W. (2009). Give My Poor Heart Ease: Voices of the Mississippi Blues. University of North Carolina Press.

Hirsch, E. (2014). A Poet’s Glossary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Khan, A. W. (2019). The Ghazal: A World Literature of Love, Loss and Longing. Bloomsbury Academic.

Kunitz, S., & Lentine, G. (2005). The Wild Braid: A Poet Reflects on a Century in the Garden. W. W. Norton & Company.

Reichhold, J. (2002). Writing and Enjoying Haiku: A Hands-on Guide. Kodansha International.

Rispetto (8 lines, Italian origin)

Nonet (9-line descending syllable poem)

Shadorma (Spanish 6-line poem)

Lai (9-line French form)

Rondel

13-14 lines

French poetic form from 14th century

Usually eight syllables per line

Rhyme scheme: ABba abAB abbaA(B)

Roundel

11 lines

English repeating form from 19th century

Rhyme pattern: ABAa BAB ABAa

Rondeau

13-14 lines

French repeating form

Rhyme pattern: ABAaABab

Magic 9

9 lines

Unique rhyme scheme: a b a c a d a b a

Reportedly inspired by the word “abracadabra”

Décima

10 lines with 8 syllables per line

Rhyme scheme: abbaaccddc

Can be structured as a single stanza or two stanzas (abba/accddc)

Often addresses social, philosophical, political, or religious themes

Ghazal

Composed of 5-15 couplets (shers)

Each line must have the same number of syllables

Includes a refrain (radif) at the end of every other line

Traditionally focuses on themes of love, loss, and longing

Canzone

Italian form meaning “song”

7-20 lines possible

Each line typically 10-11 syllables long

Triolet

French form

8 lines

Constant repetitive rhymes

First line repeated in lines 4 and 7

Second line repeated in line 8

A curtal sonnet is an 11-line poem invented by Gerard Manley Hopkins. Its key features are:

Structure: 10.5 or 11 lines total

Rhyme scheme: abcabc dcbdc or abcabc dbcdc

Meter: Often uses sprung rhythm, with 4 stressed syllables per line

Proportions: 3/4 the length of a Petrarchan sonnet

First 8 lines of a sonnet become 6 lines (sestet)

Last 6 lines become 4.5 lines (quatrain plus “tail”)